“Dr. Musselman is a passionate botanist. Walking among plant life makes him very happy, which means he is happy most of the time, except when riding in a car stuck in a long tunnel. He will stop people on the street to tell them some great news from the plant world.”

– Garrison Keillor

Edible Wild Plants

Why I am venturing from botany to blog

I have taught and written about the cuisine of wild plants for many years, one of my recent books (with former student Harold Wiggins) is The Quick Guide to Wild Edible Plants published by Johns Hopkins University Press in 2013. This is the shameless commerce section of the blog. The book is readily available through Amazon and other book sellers. See http://www.amazon.com/Quick-Guide-Wild-Edible-Plants/dp/1421408716/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1443817532&sr=8-1&keywords=quick+guide+to+edible+plants

This is the shameless commerce section of the blog. The book is readily available through Amazon and other book sellers. See http://www.amazon.com/Quick-Guide-Wild-Edible-Plants/dp/1421408716/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1443817532&sr=8-1&keywords=quick+guide+to+edible+plants

Earlier, my wife Libby and I prepared the edible plants portion for a U S Army survival manual. Since then, I have nibbled, munched, squeezed, pounded, boiled, decocted, and extracted my way across vegetation and hope to keep going.

I want to expand, examining the varied preparations from wild plants, some of which are almost tasty. I say that because wild plants and their food products so often are markedly different from our usual food, they can have a taste that would gag a maggot. For that reason my advice to those lost in the forest is to find the highest tree, climb it and look for the Golden Arches. (I’ll discuss survival plants later in this blog).

The serious naturalist and field botanist are curious about all the plants she/he encounters. And that is what I want to do in this series—explore not only well-known wild edibles, but those less familiar. For example, obtaining syrup from black walnut trees. Or witloof Belgian endive from common chicory. Or steamed sliced turions from lotus. Or one of my favorites, a cordial made from the under-appreciated fruits of deerberry (Vaccinium stamineum). And there are so many more.

From the Adirondacks to the Zagros

While most of the plants will be from the regions I know best—the Southeastern United States, the Adirondack Mountains, the Middle East—I plan to include edible plants wherever I have encountered them.

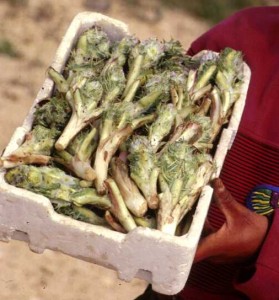

Having worked as an ethnobotanist in several parts of the world I learned that most societies do not consider some of the plants they use as “wild”, they are simply part of the traditional diet. For example, in the Zagros Mountains of Iraq one of the delicacies in spring are the young shoots of Gundelia tournefortii (Asteraceae—Sorry, no English common name). While the attraction of this thistle with an unremarkable taste and noteworthy prickles eludes me, it is in great demand. Even the spiny seeds (technically fruits) are harvested, roasted and salted—difficult to extricate the seed, smaller than a sunflower seed but just as tasty. In either form, using these plants will draw blood. It is culturally important because it links the urban Kurds with their rural past—a change unnaturally accelerated by the brutality of the Saddam Hussein regime.

Above-Freshly harvested Gundelia sold to me by a young Bedouin boy in Jordan. Below-“seeds” (technically fruits) dried and salted and sold by candy and nut merchants in Sulaimani, Iraq.

Borneo

Another example of a widely used wild food is the starch collected from sago, Metroxylon sagu (a tree rattan—a thorny plam–in the Arecaceae, the palm family) that is collected in Borneo to prepare what can only be described as bland slime, at least without the tasty toppings used to make it palatable.

Sago palm along the Belait River in Burnei Darussalam. As the picture above shows, these can be good sized trees. On the left you can see the vicious armament of the leaves.

There are more examples, all of which remind me that in the United States most citizens are far removed from the plants they eat. Our ancestors made much greater use of wild edibles; I sense a renewed interest in edible wild plants.

Usual Warnings

The usual warnings are necessary—consider allergies, plants collected from polluted sites, variability of wild plants (much greater than cultivated plants), deadly look-alikes. I’ll try to include all the usual suspects. Bottom line: don’t eat unknown plants.

What to expect

I would like to do a blog a week and will start with plants available in the fall, beginning with chickory. Stay tuned.

Lytton John Musselman

Old Dominion University

lmusselm@odu.edu

Leave a Reply