Pedagogy Online

Welcome to my page devoted to Pedagogy Online. In this page, you will find sections that feature my approach to Online Literacy Instruction (OLI) in theory and practice according to established learning outcomes of composition studies.

- Pedagogy First in Online Literacy Instruction

- Considering Important Terminology: Affordances

- Linking Affordances of Technologies, Contexts of Delivery, and Learning Outcomes in OLI

- Teaching Rhetorical Knowledge

- Teaching Information Literacy

- Teaching Writing as a Process

- Teaching Conventions

- Works Cited

Pedagogy First in Online Literacy Instruction

As Cargile Cook argued in 2005, pedagogy should be foregrounded in any approach to online literacy instruction (OLI). Only after learning outcomes are considered should the online instructor then plan how assignments “might be translated into online instructional activities” (61). Furthermore, Edward M. White’s suggests in Assigning, Responding, Evaluating that writing teachers triangulate student exposure to learning outcomes in (1) assigning, (2) responding to, and (3) evaluating their work. As such, students encounter writing assignments inspired by clearly defined learning outcomes and receive feedback from the instructor that aids student success with the final evaluation. This is also what Harris et al. might refer to as “Call for Purposeful Pedagogy-Driven Course Design in OWI,” in that writing instructors should strive to facilitate “environments where each reading, activity, assignment, and assessment correlates with the course learning outcomes.” Clearly, myriad scholars agree that learning outcomes be foregrounded, as we endeavor to facilitate (online) literacy instruction.

Considering Important Terminology: Affordances

The axiom on affordances across multiple disciplines is attributed to James Gibson who is often quoted as saying “Perhaps the composition and layout of surfaces constitute what they afford.” As such, when encountering objects, the user is able to “directly perceive” not only the objects, but also how they might be utilized in terms of “values” and “meanings.” Furthering this notion of affordances as based in meaning, Cope and Kalantzis interpret Gibson’s term “affordance” as “meaning (that) is shaped by the materiality of the media we have at our disposal” (1). Accordingly, to see an object is to also witness how the object might be utilized as a means to some end. We do not simply see objects; we see also what the objects afford us. This is an important distinction to make in OLI, as the focus of the materials designer is placed on the user experience. In designing learning materials, we must ask what the student-user will “directly perceive” as the educational task.

Upon considering the pervasiveness of the term “affordance” across multiple disciplines, Chong and Proctor offer important clarification on how the semantic value of the term has become muddled. Specifically, Chong and Proctor critique the “injudicious use of the term affordance in the human factors field,” which has led to “misusing terms unintended for the field” (129). Still, the utility of the term “affordance” remains undeniable. As such, short of abandoning the term entirely, Chong and Proctor suggest that writings using the term “affordance” minimally “draw clearer lines between Gibson and the researchers that have followed him” by naming and clarifying “what the differences between various types of affordances are” (127). For example, “perceived affordance” and “motoric affordance” are cited as examples by Chong and Proctor that help to clarify the semantic value that the writers intend.

Accordingly, in writing about affordances in OLI, it is important to delineate the kind of affordance students experience when encountering various types of online learning materials. For example, when considering the affordances of grading contracts, we might clarify what grading contracts afford students and teachers. I believe that implementing grading contracts creates both transparency affordances and equity affordances. Grading contracts afford transparency, as the grading protocol is made clear to students. Specific expectations are set for students to meet in order to earn a guaranteed grade. The grading process is transparent and not left to subjective judgments about student writing. Furthermore, grading contracts afford equity, as a measurable amount of labor is equal across the board for all students, rejecting the privilege of students who have been trained in cultures and education systems that reflect white habits of languaging. Elsewhere in my ePortfolio, I try to clarify my use of the term “affordance” based on the following contexts: rhetorical affordance, usability affordance, communicative affordance, and feedback affordance.

Linking Affordances of Technologies, Contexts of Delivery, and Learning Outcomes

With learning outcomes foregrounded in my theory of OLI, I furthermore consider how my facilitation of online education is appropriately adapted and optimized in various contexts of delivery (e.g. synchronous, asynchronous, or hybrid). Mick and Middlebrook suggest that instructors make “informed choices in OWI” by familiarizing themselves with “asynchronous and synchronous modalities in terms of the media and tools they typically use” in facilitating online learning experiences (130). As such, OLI instructors must leverage the various affordances of their instructional mode(s) to teach and encourage students to demonstrate successful acquisition of course outcomes.

Inspired by the WPA Outcomes Statement on First-Year Composition, my writing courses focus on the following learning outcomes: rhetorical awareness, information literacy, process, conventions. In the following sections, I will explore how I facilitate learning experiences based on these learning outcomes while leveraging the affordances of various technologies in my approach to OLI.

Teaching Rhetorical Knowledge

I teach rhetorical knowledge by encouraging students to consider a variety of genres and rhetorical situations for writing that are inspired by English Studies at large. Specifically, students in my composition courses encounter texts and writing prompts that are authentic to these fields of English Studies which include Professional Writing, Rhetorical Studies, Literary Studies, Creative Writing, Journalism, English Education, and Linguistics. (See figure below).

Students complete preliminary studies in all of the aforementioned emphases, writing three major essays in three respective emphasis areas of their choosing. For example, one student might write essays in journalism, creative writing, and linguistics; another might write essays in literary studies, professional writing, and English education.

Nevertheless, digital composing practices offer a number of rhetorical affordances in the demonstration of rhetorical knowledge, regardless of the student’s field of interest. For example, for a major essay, students might create a multimodal feature to the written assignment such as a graphic organizer with Google drawing, a meme, or some other kind of digital image which interprets or supports the written assignment.

Below are students examples of multimodal works that not only demonstrate their comprehension of course concepts but also their rhetorical sophistication in responding to those concepts. In the first example, one student expresses the internal conflict with expectations for code switching in job interviews, a topic we learned about in the unit on linguistics.

In class, we learned that students (and employees) have a right to their own language; still, when confronted with a moment in which this right to language is not upheld, serious consequences can ensue, a rhetorical reality that leaves many students conflicted about ways forward. “Do I code switch, suppressing my home language, and (hopefully) get the job, or do I stay true to my home language and remain unemployed?” the above student articulates via the superhero meme.

In response to this same unit in linguistics, another student, below, created a multimodal piece that captures the doubleconsciousness that code switching demands of students. This student articulates a liminal space between racialized realities, one of which is symbolized by curly hair, while the other represents straightened hair. Despite this reality, the student argues that we should “say no” to these split demands on her identity.

As the above students demonstrate, leveraging the rhetorical affordances of multimodal communication, arguably, creates a more rhetorically effective composition, and furthermore in doing so, demonstrates their acquisition of the target learning outcome.

Teaching Information Literacy

Nevertheless, to successfully demonstrate rhetorical knowledge, oftentimes the learning outcome of information literacy is also foregrounded. To be sure, the above students first considered the arguments of Vershaun Ashanti Young’s “The Problem with Linguistic Double Consciousness” before embarking on their own processes of digital composing and rhetorical sophistication.

To encourage students to engage readings independently and online is a central challenge to online literacy instruction. One study conducted by Harris et al. found that a startling single digit percentage of students surveyed thought course readings were helpful. As such, Harris et al. conclude that “student responses regarding reading illustrate problems with course design” in that students may be “left on their own to understand the readings, which may be a common feature in an asynchronous courses but also may reflect lack of instructor engagement and presence in the course.” With these findings in mind, I have developed a reading assignment sequence that presents texts as foundational to broader coursework. Within this assignment, students are not “left on their own” but rather are guided through not only how to read the assigned text but also how to use it. Below is a slide sequence which encourages students to practice information literacy in a “Reading Response” assignment. The first slide, below, is the module’s title slide.

The first content-driven slide (below) of this module simply encourages preparation for reading. Oftentimes, to practice information literacy takes attention, focus, and calm. For that reason, the first set of directions considers the student’s place and state of being. Finding a quite place to practice mindful breathing is a great first step to fully engaging an assigned text. This creates a ritual for reading, a process for engaging academic thought and learning that is embodied.

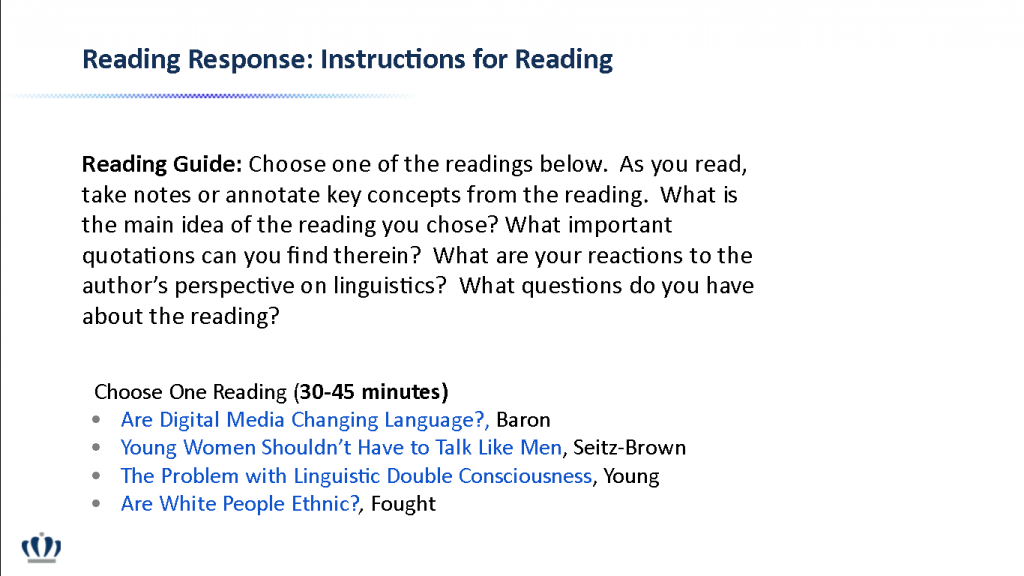

After having devoted some time to preparation, the following module slide offers instructions for reading. Importantly, these instructions are intentionally separated from instructions for writing. I believe students benefit from a slide’s focus on reading alone, which foregrounds the primary means of engaging information literacy. In this slide, students are offered a “Reading Guide,” which contextualizes how to approach the assignment. Students must not only read the words on the page, but also monitor their reading progress by focusing on main ideas and purposes presented by the author. Simply put, I hope students not only encounter the text but also leave the text having deduced a least one important point to share, respond to, or debate.

With a clear purpose for reading in mind, the following module slide encourages students to use the text in ways that serve their own purposes. Similar to the above “Reading Guide,” on the slide below, students are offered a “Writing Guide,” which again contextualizes how to approach the next phase of the assignment. As the slide’s directions state, students first review the annotations and notes they took in completing the “Reading Guide.” After reviewing their work, students then summarize the important points from the reading, offering a citation thereof. Central to information literacy as reading comprehension, and I believe that writing in response (or writing to learn) is foundational to the successful acquisition of this course goal; as such, student conclude their Reading Response assignment with their personal reactions to the text.

Nevertheless, in teaching students about information literacy–guiding them through texts and encouraging their responses thereof–a number of usability affordances present themselves in online contexts in the facilitation of this learning outcome. For example, delivering reading in online contexts enhances the accessibility of course materials. First, sharing readings online–especially Open Access readings–minimizes socioeconomic barriers to education. Simply put, in making readings available one click away, all students can access the course readings, provided they have a device and internet connection. Furthermore, presenting this module via the PPTx/Google Slides platform is easily accessible via a mobile device, as per the recommendations of Rodrigo. Secondly, I hope this Reading Response assignment heeds Nielsen’s call for accessible class content. To be sure, all assigned readings in the Reading Response module are screen readable and produced with universal design in mind to include offset headings, sans serif font, and links embedded in text descriptions. In short, this Reading Response was designed with the user experience in mind. Arguably, delivering readings in this format is a clear usability affordance to teacher and student as this content is available to a broader audience than would be a print reading.

Teaching Writing as a Process

An additional learning outcome of my freshmen composition courses relates to writing processes. Indeed, helping students establish habits of workflow in writing is crucial in their future writing lives. To help facilitate processes of writing, I heavily scaffold assignment sequences.

As previously mentioned, students in my freshmen composition courses encounter field-specific readings for which they produce a reading response. After engaging multiples steps in completing their Reading Responses, students are tasked to join a class community forum in which they are challenged with situating their reading response within a broader class discussion. Generally, the prompts in the Writing Forum task students with extending the discussion that they began in their Reading Responses. They can share their opinions on topics from readings or introduce a related topic to the forum, commenting on their peer’s responses and responding to their peers in turn.

Next, after having joined and participated in the Writing Forum, students then encounter the essay assignment that encourages them to leverage their initial reading response, developed by the community forum, as invention for a longer essay. The figure below offers a visual representation of this assignment sequencing, and I hope meets the call of Harris et al. in that “the connections among these different parts of an OWC are the heart of purposeful pedagogy-driven course design.”

Working through interconnected assignments, furthermore, encourages students to practice writing as a reciprocal process. Working through three levels of writing and revision requires students to critically analyze their writing via reading, (re)invention, peer feedback, and instructor conferences. The very nature of coursework is process. Also, as students progress through the scaffold, grade weight increases; thus, students are responsible for low-risk assignments which become full-fledged, semester projects.

Feedback-Focused Processes

Nevertheless, process is not limited to how work is assigned in my courses but also in how I make myself available to students. I believe an invaluable role we play as instructors is to offer students feedback before, during, and after they write. One example, explained below, of a pedagogical intervention I have implemented balances the learning outcome of acting on instructor feedback with the communicative affordances of the asynchronous mode.

The CCCCs Position Statement on Principles for the Postsecondary Teaching of Writing states that “secondary writing instruction . . . depends upon frequent, timely, and context-specific feedback from an experienced postsecondary instructor.” Furthermore, students view instructor feedback as invaluable. In Rendahl and Breuch’s study of learners in first year writing courses, “Students reported that they valued interaction with and feedback from their instructor” (308-309). The importance of instructor feedback is emphasized in Boyd’s study of online and hybrid composition courses, which found that students “rated their instructor’s feedback as most important” among various strategies of teaching and learning (239).

Despite the value of instructor feedback, barriers to communication must be negotiated by leveraging the communicative affordances of the asynchronous and synchronous modes. Example methods of online feedback which I leverage include using the comment feature in Google docs in response to student writing in ways that encourage students to use the “reply” feature, meeting for Gchat discussions for a typed conversation, and encouraging student attendance to virtual office hours via Zoom.

Regarding the latter example, significant barriers to office hours attendance exist in online contexts, to include scheduling and perhaps at the most basic level, an understanding of the purpose of such a meeting. Students might not be aware of office hours. Even if they are aware of office hours, will students remember where to find postings of office hour availability? Even still, some students who are aware of the opportunity to speak live with their professor are afraid to do so. The power distance between instructor and student might be too great for students to traverse on their own. Still, negotiating these barriers is crucial to successful online instruction, especially if synchronous conversations are among the preferred pedagogical strategies of the instructor and student.

One way to encourage attendance to virtual office hours is to create “pop-up” office hours, which are advertised via a multimodal flyer. The below figure illustrates one such “pop-up” flyer I designed to encourage students to attend a synchronous session.

I find that communicating availability to students multimodally, in part, reduces the power distance or intimidation students feel when meeting a professor for the first time. Furthermore, framing synchronous availability on a “pop-up” basis might be understood, metaphorically, as antithetical to the ivory tower. “Pop-up” time might be inferred to be informal, low-stakes, and less intimidating to “visit.” There is furthermore an understanding that a “pop-up” session is temporary and must be attended while available, which may additionally encourage students to attend.

Furthermore, the multimodal flyer for synchronous availability leverages the pervasiveness of smartphone technology available to students. As noted by Rodrigo, our Online Writing Instruction (OWI) should accommodate the reality of smartphone usage among students as the primary means of accessing course content. As such, teachers should leverage students’ use of smartphones in their OWI, “adapting to and adopting strategies for the growing number of students using mobile devices” (500). Viewing OWI through the perspective of a mobile device, ideally, students will find the support they need one tap away from wherever they are.

Teaching Conventions

Knowledge of grammatical and citation conventions is the final learning outcome I teach in my freshmen composition courses. While I do offer stand-alone lessons on conventions, I also recognize how “conventions” are often designed to uphold language discrimination. To be sure, I do not demand that my students code-switch or utilize white mainstream English in their compositions. Still, Asao Inoue furthermore concedes that it may be important that students “learn about the politics of literacy and how one’s language is judged in the world from those politics” in developing an understanding of what it means to practice (and break) conventions (273).

As such, I leverage the feedback affordances of digital polling, such as is offered on the Zoom platform, to survey students levels of interest in learning more about grammatical and citation conventions. Based on their interest level, I deliver lessons which are unique to each respective class. For example, if one group is interested in a “grammar refresher” but another class is interested in learning about “advanced grammar,” I oblige. There cannot be a one-size-fits-all approach to the teaching of conventions, and lecturing students based on their interest levels leads to better uptake of concepts, in my opinion. Students are in control of the lesson they learn. Furthermore, I leverage the above mentioned tools for feedback–Google comments, pop-up flyers–to offer students feedback on conventions on an idiosyncratic bases.

Finally, our discussion and learning of conventions are not limited to MLA or white mainstream English conventions. Journalists practice very different citation conventions–often by simply naming a source in the narrative–for example. I believe it is important for students to track their sources, to give credit when due and to call out misinformation when appropriate; however, I do not believe it is the place of freshmen composition to be a service course to the university in which we spent an undue amount of time on, say, where periods fall in block quotes or the order of information in a full-text citation. In my experience, many instructors use these features of student writing to manage their own workload when grading, at the expense of the student. Furthermore, with regard to grammatical conventions, students in my freshmen composition courses also learn about other English grammars to include Black Language, Southern, and Chicano English. In that way, the purpose of a curriculum on conventions is to enrich, not erase the diverse array of “conventions” in American Englishes.

Works Cited

Boyd, P. W. (2008). Analyzing Students’ Perceptions of Their Learning in Online and Hybrid First-Year Composition Courses. Computers and Composition, 25(2), 224-243.

Chong, Isis and Robert Proctor. (2020). “On the evolution of a radical concept: affordances according to Gibson and their subsequent use and development.” Perspectives on Psychological science. Vol. 15(1) 117-132.

Cook, K. C. (2005). An argument for pedagogy-driven online education. In K. C. Cook & K. Grant-Davie (Eds.) Online Education: Global Questions, Local Answers. Routledge, pp. 49-66.

Gibson, J.J. (1979) The ecological approach to visual perception. Boston, MA: Moughton Mifflin

Harris, H. S., Melonçon, L., Hewett, B. L., Mechenbier, M. X., & Martinez, D. (2019). A call for purposeful pedagogy-driven course design in OWI. ROLE: Research in Online Literacy Education, 2(1), http://www.roleolor.org/a-call-for-purposeful-pedagogy-driven-course-design-in-owi.html

Inoue, Asao B. (2019). Labor-Based Grading Contracts: Building Equity and Inclusion in the Compassionate Writing Classroom. The WAC Clearinghouse; University Press of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.37514/PER-B.2019.0216.0

Kalantzis, Mary & Cope, William. (2020). The Changing Dynamics of Online Education: Five Theses on the Future of Learning. 10.13140/RG.2.2.25664.97287.

Mick, C. S., & Middlebrook, G. (2015). Asynchronous and synchronous modalities. In B. Hewett & K. E. DePew (Eds.), Foundational Practices of Online Writing Instruction (pp. 129-148). WAC Clearinghouse. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/owi/chapter3.pdf

Nielsen, D. (2016). Can everybody read what’s posted? Accessibility in the online classroom. In D. Ruefman & A. G. Scheg (Eds.) Applied Pedagogies: Strategies for Online Writing Instruction, pp. 90-105. Utah State UP.

Rendahl, M., & Breuch, L.-A. K. (2013). Toward a complexity of online learning: Learners in online first-year writing. Computers and Composition, 30, 297-314.

Rodrigo, R. (2015). OWI on the go. In B. Hewett & K. E. DePew (Eds.) Foundational Practices of Online Writing Instruction, pp. 493-516. WAC Clearinghouse.

White, E. M. (2006).Assigning, responding, evaluating: A writing teacher’s guide. New York, NY: Bedford St. Martin.

Young, Vershawn Ashanti, The Problem with Linguistic Double Consciousness https://drive.google.com/file/d/10KApciuW4eq_VTIz4Hbw5MGZ21J7x–A/view?usp=sharing

Recent Comments