Right now is a great time to be studying the history of philosophy. There are a lot of philosophers doing innovative work critically rethinking the historical narratives which have been more-or-less dominant since the 19th Century, and new translations are making previously marginalized or ignored authors, texts, and traditions more accessible or sometimes accessible for the first time. For example, the translation of Amo’s Impassivity that we read was published in 2020, and is a very significant improvement over the previous English translation. (With the exception of the end of the work, “TANTUM,” which the new translation renders as “END” rather than the previous translation’s obviously preferable “THAT IS ALL.”)

For our midterm, I’m asking you to read another work which has also has a new, much-improved translation—in this case, published just four months ago, in November 2023. The only previous complete English translation of the work was Claude Sumner’s 1976 translation.

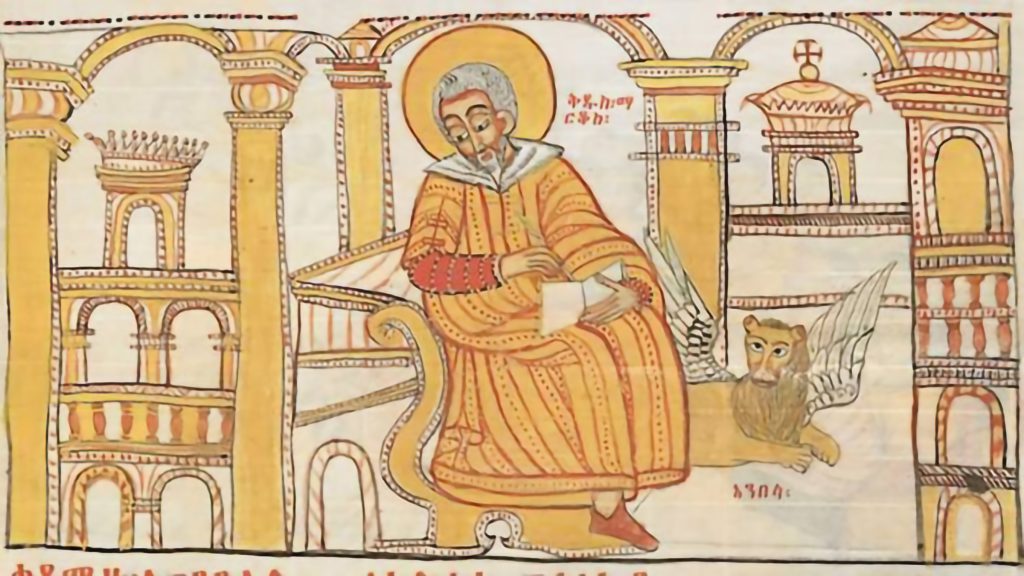

Zera Yacob’s Hatata (or “Inquiry”) is a fascinating work of Rationalist Modern philosophy, particularly of note because we think of Rationalism and Modern philosophy as being distinctively European movements and Zera Yacob was an African philosopher in Africa. The events at the start of Zera Yacob’s Hatata took place in the northern Ethiopian city of Aksum, 3231 miles away from Amsterdam, where Descartes was writing his Meditations at that exact time. Their contexts are more similar than it might seem: Zera Yacob was working within a longstanding Ethiopian philosophical tradition which had a basis in Greek, Roman, and Islamic sources, many of which were also part of the European tradition. Both Zera Yacob and Descartes strongly engaged with Christian Patristic philosophy (e.g. Augustine), although Zera Yacob did so by way of Byzantine philosophy and the Tawehedo and Coptic churches while Descartes did so by way of Latinate European philosophy and the Catholic and Protestant churches. Both were even familiar with the Jesuit tradition specifically! The Jesuit order adopted a standardized curriculum, which at this time emphasizing relied heavily on the works of the Spanish-Sephartic (converso) philosopher Francisco Suárez. Descartes knew the curriculum through his Jesuit college education; Zera Yacob knew it from being on the receiving end of Jesuit missionary evangelism.

While these similarities may be more significant than you might expect, the differences are still great. In the European context, new mathematical and technological advances (e.g. the telescope) had led to newfound questioning of the basis and possible unrealized potential of human knowledge, which would lead to the development of modern science. Descartes draws on many European scholars who were important to the intellectual foundation of modern science but who weren’t part of the Ethiopian context at all, e.g. William of Ockham, the Oxford Calculators, Francis Bacon, and Galileo Galilei. So those are resources and influences that Descartes had that Zera Yacob didn’t. But we should also ask what was in the Ethiopian tradition that wasn’t in the European tradition.

This is a much more difficult question to answer. The Ethiopian philosophical tradition is not very accessible in English or, as far as I know, any other living language. Most work in the tradition was written in Ge’ez, which is sort of like Latin is for English speakers: it hasn’t been a living language in a thousand years, and is now only relevant to historical scholarship and to Orthodox and Catholic church services. As historical work on the tradition continues, though, we get a picture of a tradition that was very much in conversation with the larger world. For example, although the 17th/18th Century Hatata of Zera Yacob and Hatata of Walda Heywat were composed in Ge’ez, older major works in the tradition were adaptations and expansions of works originally written in Greek and Arabic, including The Physiologue in the fifth Century, The Life and Maxims of Skendes in the 11th Century, and The Book of the Wise Philosophers in the 16th Century. Tracing the tradition further back before the origin of Ge’ez script would depend on written accounts from outside of the tradition, which presents serious problems. There are ancient accounts of the Ethiopian people and their beliefs—for example, Xenophanes wrote in the 5th Century BCE,

“Ethiopians say that their gods are snub-nosed and black; Thracians that theirs are blue-eyed and red-haired. If horses or oxen or lions had hands, or if they could draw with their hands and produce works like men, horses would draw the figures of the gods as similar to horses, and oxen as similar to oxen, and they would make the bodies of the sort which each of them had.”

But it’s difficult to know whether the “Ethiopians” discussed by the ancients are actually Ethiopians, since the Greek “Αἰθίοπες” is a vague description meaning something like “those of burnt face,” and seems to have also referred to other dark-skinned peoples, most notably the Kushites and Nubians, but not all other dark skinned peoples (e.g. not the Egyptians and Colchians).

Even all this only addresses intellectual foundations and influences; to get a full view, we would need to consider political, economic, social, and environmental differences and more.

Chike Jeffers, a Canadian scholar of African and Africana philosophy, said

“There is a sense in which Locke and Descartes share a modernity that Zera Yacob does not, a point that need not lead us to deny that Zera Yacob is a modern philosopher, but rather to say that he inhabits a different modernity. (“Rights, Race, and the Beginnings of Modern Africana Philosophy,” in The Routledge Companion to the Philosophy of Race.)”

What is it that makes both Descartes and Zera Yacob “modern”? But in what sense are their modernities different modernities? Those questions are larger than you could answer in this assignment, but at base those are the questions I want us to have in mind.

For your midterm,

1. read Zera Yacob’s Hatata,

2. take notes on similarities and differences with our other texts, especially but not only Descartes’s Meditations, and especially regarding our major themes,

3. develop a thesis/claim/argument about some systematic or fundamental connection or divergence between Zera Yacob’s Hatata and Descartes’s Meditations (and its basis in the other texts we read), and

4. write a paper explaining and defending this thesis, citing specific passages in the relevant works.

Specifications:

• Steps 2, 3, and 4 are separate because I want you to make note of a wide variety of connections and divergences before taking a particular perspective on it and narrowing down what you want to write about. This means that you shouldn’t be writing on your first thoughts, but waiting to get a bigger-picture view first. It also means you shouldn’t try to include all of your notes in the paper. Focus on clearly establishing some specific claim; you won’t be able to address every worthwhile thought you have about these texts.

• There isn’t any single or specified “right answer” or hidden rubric where I’m expecting you to find some particular thing or set of things. You’ll be assessed based on the case that you put together for whatever claim you want to make—it should show a good understanding of Descartes and a knowledge of the parts of the text relevant to your claim, should show skill in the kind of contextual interpretation that I’ve trained you in, should show a good basis in the texts, and should provide clear reasoning for your claims.

• There is no need to do any research outside of our assigned texts. There is research out there comparing these texts, though, and you can use it if you like. This might be a good way to go if you don’t have any topics you feel confident about after your read-through and note-taking. If you use any research, cite every source used, even if you’re not quoting it directly. Any citation style is fine, and it’s fine to use a citation generator, and I won’t worry about whether you’ve got the citation style totally correct. If the source is online, include a link!

• A reminder from the syllabus: You should not be using any form of generative AI in any way without clearing it with me first.

• Minimum word count is 1800 words, but that would be a pretty tightly-worded paper. If you find yourself writing in more of a conversational and wide-ranging style, you might go significantly over that, and that’s totally fine. If for some reason you’re struggling to reach that minimum word count, just get in touch with me. I’ll ask you some questions about what you’ve got, and answering those questions will get you over that minimum.

• The midterm should be submitted anytime on Tuesday, 19 March, up until and including the morning of Wednesday, 20 March.