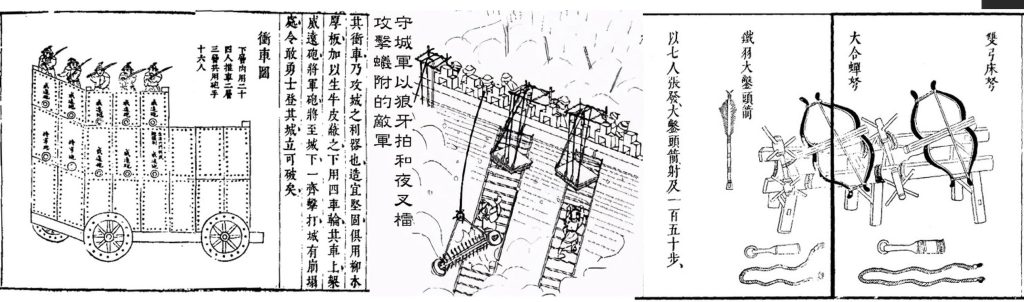

Figure 1: Diagrams of some defensive war machines and devices from Part V of the Mozi. Left to right: “platform (moveable) walls”, “cylindrical caltrops” and screens, and a “joined crossbow”.

墨子 (Mozi, 470–391 BCE) was a philosopher during the early Warring States period in China. This was a time of great uncertainty and unrest, which resulted in great innovation and development in philosophy—indeed, the early Warring States period is also known as the Hundred Schools of Thought period. During this time, Ruism (typically called “Confucianism” in Anglophone philosophy) was developed into a full philosophical system by its three great Ancient masters, 孔子 (Kongzi, aka Confucius, 551–479 BCE), 孟子 (Mengzi, aka Mencius, 371–289 BCE), and 荀子 (Xunzi, 300–237 BCE). Daoism was also formulated during this period by combining views attributed to the possibly-fictional more-ancient-than-Ancient philosopher 老子 (Laozi) with aspects of Ruism and other elements of the Naturalists, also called The School of Yin Yang. (You may be able to guess at least one of the elements of The School of Yin Yang that Daoism adopted.) The Warring States period ended in 221 BCE with the unification of China through military conquest, creating the Chinese Empire of the Qin dynasty. The Emperor Qin ended the great war of ideas as well, declaring Legalism the state philosophy of China, and ordering the destruction of texts from other philosophical traditions, and the killing of their philosophers in an order known as 焚書坑儒 (The Burning of Books and Burying of Scholars).

Obviously, the success of that effort was limited, and after Emperor Qin was overthrown by Liu Bang, establishing the Han dynasty, Ruism became the favored philosophical system, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Looking back to the thought of the Hundred Schools of Thought period is interesting in many ways. We’re used to thinking of the major players in Chinese philosophy as being Ruism, Daoism, Buddhism, and of course Maoism, but the Hundred Schools of Thought period was before Marxism or Buddhism came to China, and saw the creation of Daoism and the mature formulation of Ruism. Stranger still, during this period there were many “schools of thought,” but only two organized schools that provided systematic instruction and training, and while one of them was Ruism, the other was a belief system that fell into obscurity following the end of the Warring States period: 墨家 (Mohism). Chinese philosophers began to revive interest in Mohism in the 19th Century, seeing that its many commonalities with European thought of the time might help China to adapt and respond successfully as connections with Europe deepened at that time. More recently, Anglophone philosophers have become interested in Mohism, sometimes at first as a kind of oddity—turns out there were utilitarian ethicists in China 2500 years before Bentham invented it!—but increasingly for its own sake.

Like with most (surviving) texts of the Hundred Schools of Thought period, the book of the school of thought is named for its master, so the Mohist text is called “the Mozi,” where “Mozi” just means “Master Mo”. It’s possible that 墨翟 (Mo Di; Master Mo) himself wrote some of it, but it’s not a given. It is however definitely the case that he didn’t write all of it, not even all of the parts that are specifically attributed to him.

The writing style of the Mozi is distinctively different from other Ancient Chinese philosophy. Where other works of the era have poetic and aphoristic elements and often make arguments implicitly through imagery, metaphor, and legend, the Mozi tends to be wordier, less refined, and more direct. This reflects the lower social class of 墨翟 himself and of most of those who became Mohists. It was a working-class movement, and its core commitment to 兼愛 (“universal love” or “inclusive care”) reflects that.

The Mohists saw the wealth and privilege of the elite as wasteful and selfish, and saw the Ruist docrine of caring most for those closest to you as part of the problem. They held that the benefit of all people should have equal importance, and that we should make decisions impartially and objectively, giving power and authority on the basis of merit, and making choices that avoid unnecessary expense and provide for the benefit of all. This is what led to their strong anti-war stance. They saw the many wars of this period as benefiting only the rulers, and doing so at the expense of the poor, and as resulting in nothing but shifting this land or wealth from this wealthy family over to some other wealthy family, destroying much of value in the process. It’s worse than a zero-sum game, but even more importantly for the Mohists, there isn’t even any gain to be had from an impartial view! If you care about all people, you should love those you’re attacking just as much as you love your own clan or countrymen. So why would anyone support an offensive war except based on greed or hatred?

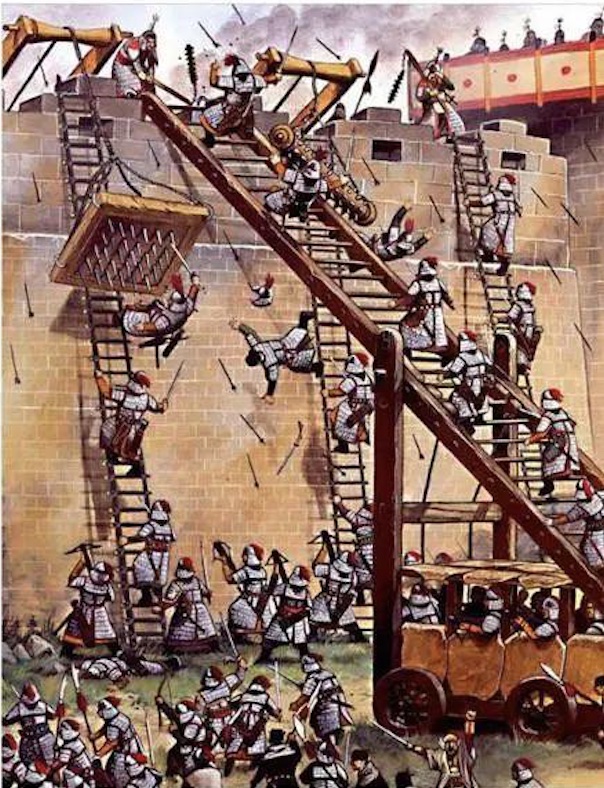

This being literally the “Warring States” period, this position was a matter of practical relevance, and the Mohists approached the issue practically as well as intellectually. The Mohists were a paramilitary organization, trained in defensive warfare and military engineering as well as in ethics, political philosophy, logic, argumentation, and of course geometry. They sought to end war by converting rulers to their belief system, and also by defending any city under attack—even defending one side of a conflict in one battle before rushing to the aggressor’s side to protect them from retaliation—in order to ensure to the greatest extent possible that nothing could be gained by choosing to wage war.

To me, the thing that’s most Modern (or “Modern”?) about the Mozi is that it sets out new doctrines based on reason, observation, and argumentation rather than developing or justifying traditional moral, political, and spiritual doctrines. Unlike Ruism and Daoism, it starts out here and now and sorts through tradition to see what is and what isn’t worth keeping, and is perfectly willing to follow logic and virtue in radically new directions, if that’s where they lead. It turns out those new directions include ideas and arguments about justice that seem to be plucked from the far future . . . as well as a whole entire manual for waging military defense, including very detailed plans for barriers, traps, and defensive war machines.

Figure 2: Mohist defenses against Cloud Ladders (Ch. 56, pp. 585–590) and the ‘Ant Approach’ (Ch. 63, pp. 609–615)

For your final,

1. read the selections I’ve picked out for you from the Mozi,

2.take notes on similarities and differences with our readings from Hobbes and Locke (and others, if you like, but Hobbes and Locke will be the main connections),

3. develop a thesis/claim/argument about maybe two or three issues that these authors have as common concerns or ideas, and how they approach those concerns or ideas similarly or differently, and

4. write a paper explaining and defending this thesis, citing specific passages in the relevant works.

Specifications:

• Steps 2, 3, and 4 are separate because I want you to make note of a wide variety of connections and divergences before taking a particular perspective on it and narrowing down what you want to write about. This means that you shouldn’t be writing on your first thoughts, but waiting to get a bigger-picture view first. It also means you shouldn’t try to include all of your notes in the paper. Focus on clearly establishing some specific claim; you won’t be able to address every worthwhile thought you have about these texts.

• There isn’t any single or specified “right answer” or hidden rubric where I’m expecting you to find some particular thing or set of things. You’ll be assessed based on the case that you put together for whatever claim you want to make—it should show a good understanding of Descartes and a knowledge of the parts of the text relevant to your claim, should show skill in the kind of contextual interpretation that I’ve trained you in, should show a good basis in the texts, and should provide clear reasoning for your claims.

• There is no need to do any research outside of our assigned texts. There is research out there comparing these texts, though, and you can use it if you like. This might be a good way to go if you don’t have any topics you feel confident about after your read-through and note-taking. If you use any research, cite every source used, even if you’re not quoting it directly. Any citation style is fine, and it’s fine to use a citation generator, and I won’t worry about whether you’ve got the citation style totally correct. If the source is online, include a link!

• A reminder from the syllabus: You should not be using any form of generative AI in any way without clearing it with me first.

• Minimum word count is 1800 words, but that would be a pretty tightly-worded paper. If you find yourself writing in more of a conversational and wide-ranging style, you might go significantly over that, and that’s totally fine. If for some reason you’re struggling to reach that minimum word count, just get in touch with me. I’ll ask you some questions about what you’ve got, and answering those questions will get you over that minimum.

• The midterm should be submitted anytime on Thursday, 25 April, up until and including the morning of Friday, 26 April.