The most popular vintage nibs weren’t much different from the nibs made today—steel, sometimes gold-plated, rigid, in fine or medium. Specialty nibs, however, were easier to find back when fountain pens were the standard pen, and some of these nibs require some explanation.

Extra-fine nibs:

Extra fine nibs were made, but “extra fine” was not a common designation. Instead, “fine” nibs covered a wide range, from extra-fine to medium, depending on the manufacturer and sometimes it seems the individual nib. Of course, today, “fine” doesn’t mean the same thing in a Japanese-made nib as it does in a German-made nib, so this variability isn’t unique to vintage pens.

Stub and italic nibs:

Rare in vintage pens as today, these nibs provide some line variation for everyday writing—they are less wide than nibs used for calligraphy.

Spoon-tip nibs:

Some nibs were given spoon-shaped writing surfaces rather than using tipping material, such as iridium. This was especially common during the Depression to make pens more affordable. Spoon nibs can be very nice, smooth writers, but they have a smaller “sweet spot” than regular tipped nibs—it’s easier to angle or rotate the pen enough to become scratchy or to result in poor ink flow.

Gold and silver nibs:

Nibs made in solid gold (usually 14K) and palladium silver were more common in the past. They usually have a “softness” their feel on the page even when they are rigid rather than flex nibs.

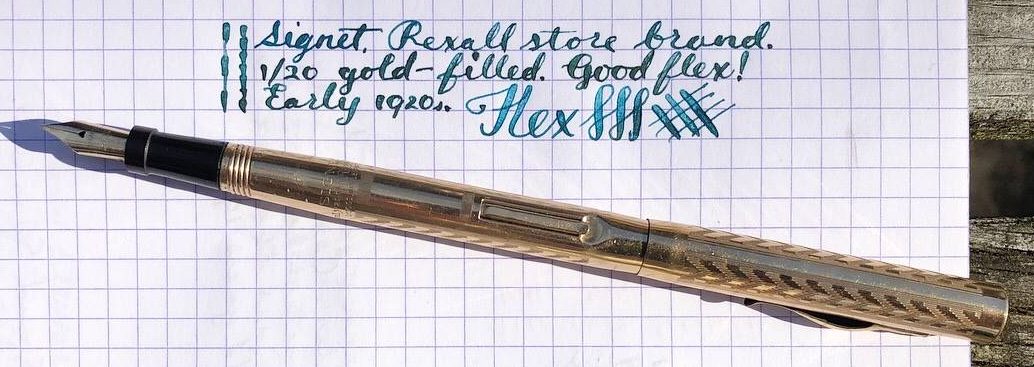

Flex nibs:

They don’t make flex nibs like they used to—they can’t. Flex nibs today are far more stiff than they once were, and it seems like the technique of making vintage-level flex nibs has been lost. Today, you can get steel flex nibs that are fun, but aren’t really like vintage flex nibs, or you can get expensive ($100+) gold flex nibs which still only approximate vintage flex. For this reason solid-gold vintage flex and semi-flex nibs are valuable and sought-after.

Writing with a flex nib requires some practice. Pressing down gently produces line variation as the tines spread, but the nib should only be flexed on the down stroke, and should not be flexed to its full breadth in regular writing, else risking that the nib be sprung. Getting flex nibs to write well may also require the right ink and paper. Ink that’s too dry won’t keep up with the flow rate demanded by a flexed flex nib, resulting in railroading, but a wet ink may lay down so much ink through a flex nib that it causes writing to feather and show through even high-quality paper. I test flex nibs with a variety of inks and papers, and when I list a pen as having a flex or semi-flex nib, you can expect that—unless otherwise noted—I have adjusted the flow to produce good flex writing on high-quality paper with a range of inks. Nonetheless, you may still need to experiment with different inks and papers to find the write match for the pen and how it performs in your hand.

Oblique nibs:

These nibs are cut at an angle to accommodate writers who prefer to rotate their pens a bit—often, left-handed writers. Richard Binder has a nice explanation with great diagrams, so I’ll just refer you there.