Several years ago my coauthors and I did a study looking at the 2008 and 2010 CCES survey data in order to try to estimate the prevalence of non-citizen participation in US elections.

The basic theoretical idea behind the study from my perspective is the literature on the calculus of voting or costs of voting. For non citizens the costs are higher (its illegal to vote for instance) but just because something costs more doesn’t mean that people won’t sometimes decide the costs are worthwhile (or won’t sometimes ignore the costs or miss the fact that they will pay costs). People speed. People use illegal drugs. People break a variety of laws. For some people the benefits seem to outweigh the costs. So, the question was how many non-citizens participate in US elections despite the higher costs?

A challenge that we sought to address in the appendix of that paper, and sought to address further in a working paper available on this website from 2017 involved the question of whether the respondents were actually non-citizens. Critics wondered whether perhaps the people who said they were not citizens had made a mistake and accidentally indicated that they were not citizens when in fact they were citizens after all. Perhaps the small percentage of non-citizens who said they voted (and small the percentage of non-citizens who had cast a vote according to the voting record matches performed by Catalist) were actually citizens who had mistakenly selected the wrong box when identifying their citizenship.

I am grateful that in 2020 the CCES has followed a suggestion I originally made to the principal investigators in early 2016 — they asked two questions about citizenship status. Here’s a screen shot of the survey instrument with the first question:

And here is a screen shot of the survey instrument with the second question which follows up on the first question.

The skips in this survey instrument are a little bit confusing. It’s not entirely clear that they managed to do what I hoped they would which was to double-ask people who said they were non-citizens if they were in fact non-citizens. But let’s assume that in fact the skips were set up properly to accomplish that verification, and see where that takes us.

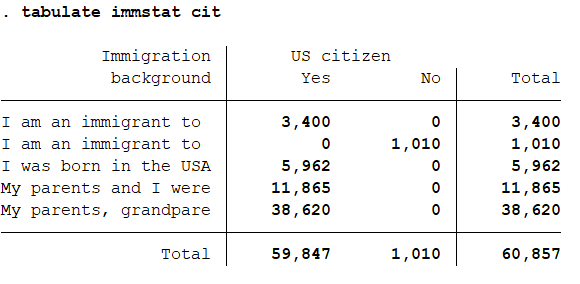

The first place it should take us is to examine the crosstab between these two questions.

The match is perfect (too perfect perhaps?). This could reflect a poorly structured set of skips that forced it to be perfect. Or it could reflect that this is not a hard question to answer, one that most people answer accurately without much difficulty, contrary to the speculation by some critics to the contrary. And it could also reflect self-correction. Perhaps respondents who gave the incorrect answer to the first question went back and fixed it when they got the wrong set of options on the next survey page.

The argument from our critics was in part that the people who said they were non citizens and said they voted and/or had a voter file match with a recorded vote were actually citizens. If the questions were asked properly (i.e. in a way which allows us to use them to verify that someone who was not a citizen was in fact not a citizen by asking them a similar question again) then we are looking at a group of respondents who indicated twice in succession that they were in fact not citizens. While it’s possible that these were people who were intentionally lying to the survey about their citizenship status, the possibility that someone could have accidentally indicated that they were a noncitizen TWICE should be MUCH lower than the possibility of making that mistake once. For instance, our 2017 working paper estimated that citizens mistakenly indicate that they are non citizens less than half of one tenth of a percent of the time. Multiple 0.0005*0.0005 and you get a really really small number. In other words, if these questions are working as they should be, we can be a lot more confident that the people who say they are not citizens are in fact not citizens.

What about registration and voting among this group of people 1010 of them in all who twice indicated that they were noncitizens?

The CCES has not yet released their voter file match “vote verification” data for 2020 so we cannot yet look at anything beyond self reported registration and voting. I would also like to note that I am reporting here raw frequencies — I have not done any weighting of the data at this point. Since weighting can improve the accuracy of survey estimates, this is something to put on the to do list. As in the 2014 article, there is a case here for doing a custom weighting of the non-citizen subsample to try to make sure it is representative of non-citizens as a whole. With those caveats in mind, let’s proceed.

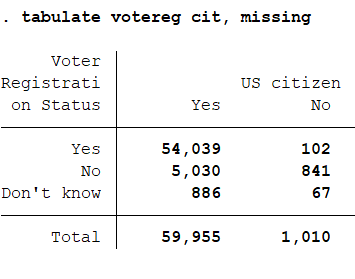

The CCES has two waves, a pre-election survey and a follow-up post-election survey. The pre-election survey includes a question about voter registration status. Here is a tabulation of that question alongside the citizenship status question.

As reported in the tabulation, 102 of the 1010 self reported non-citizens indicated that they were registered to vote, while 67 indicated they did not know, and 841 indicated that they were not registered to vote. The portion who reported that they were registered to vote was 102/1010 = 10.1 %

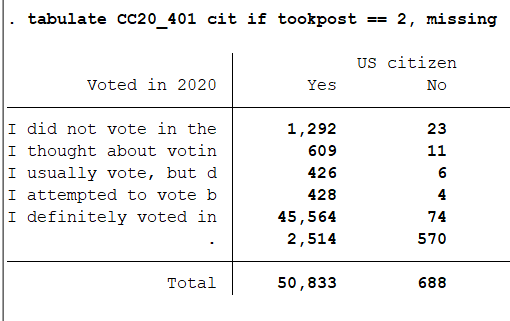

As is always the case in surveys, there was some attrition between the pre-election wave and the post-election wave. Overall, 688 of the twice self-reported non-citizens took the post-election survey and thence had a chance to answer the question concerning whether they voted in the election.

Of those 688 respondents to the second wave, 74 indicated that they had “definitely voted” in the election. 74 / 688 = 10.7% of those who took the second wave, and 74 / 1010 = 7.4% of the whole sample of self reported non citizens. These numbers are quite similar to those reported for 2008 in my coauthored 2014 article in Election Studies.

One other note. The survey also asked questions about presidential preference and voting mode. Responses to those questions might be of interest.

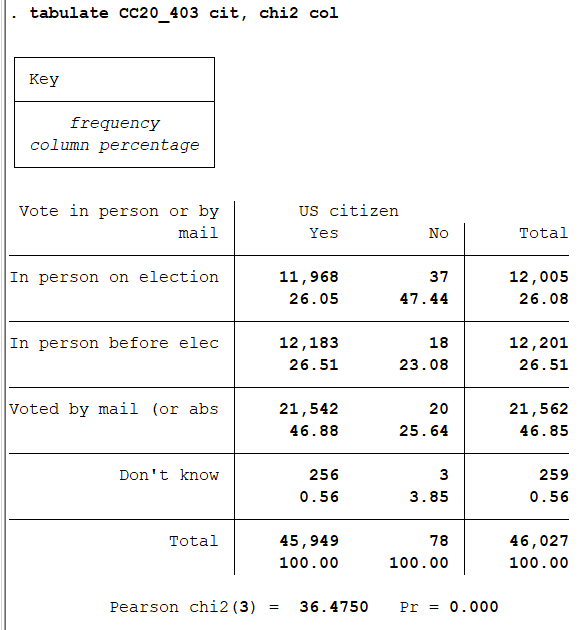

First voting mode.

As shown in the crosstabulation above, a substantially larger portion of non-citizen voters indicated that they voted in person, compared with US citizens in the sample (47 percent versus 26 percent) with a commensurately lower portion of non-citizen respondents indicating that they voted by mail (26.6 percent versus 46.9 percent). This difference is highly statistically significant. Self reported non-citizens seem to like voting in person compared to the general public.

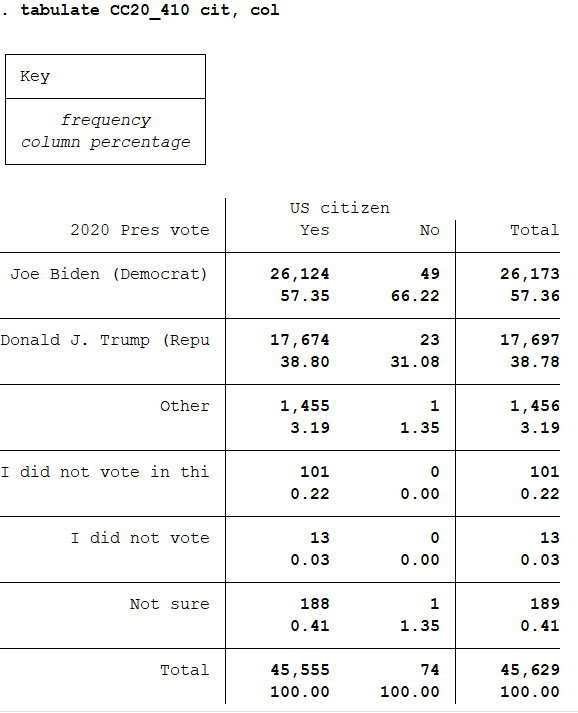

In some elections (2012 for instance) self reported non-citizens reported supporting the Democratic candidate by very large numbers. That wasn’t really the case in 2020. The tabulation below looks at the portion of the citizen and self-reported non-citizen CCES sample that said they backed each presidential candidate. Joe Biden received 66 percent of the self-reported non-citizen vote, whereas Trump managed 31 percent. This is better than Biden’s margins in the overall sample, but the difference is not all that large, and it isn’t statistically significant in this analysis. Overall, a relatively large portion (almost 1/3) of non-citizens who said they voted also said that they voted for Donald Trump.

So, let’s step back for a moment to reflect on the 2020 CCES. The big picture about non-citizen voting remains relatively unchanged.

I think the key thing people of all ideological stripes sometimes miss (because it’s hard to grasp and hard to convey) is that the level of non-citizen voting in the US remains uncertain and difficult to estimate. Critics have argued that the numbers in my earlier study could reflect simply measurement error https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/trump-noncitizen-voters/, and they have an argument to make. But clearly there is some non-citizen participation, as the occasional prosecution of a non-citizen voter indicates, and the critics may be exaggerating the level of measurement error as my colleagues and I argued a few years ago in this working paper https://fs.wp.odu.edu/jrichman/wp-content/uploads/sites/760/2015/11/AnsolabehererResponse_2-8-17.pdf, and as the double-checking of non-citizen status in the newest version of the CCES also seems to suggest. The 538 piece has a data visualization box where you can set up scenarios which was a great idea. Unfortunately, the minimum level of response error allowed in the slider is more than twice the error rate my colleagues and I estimated in the working paper, and their defaults are more than 20 times higher. I know that their point is to illustrate the potential presence of the problem, and they do that effectively, but this risks giving a misimpression about the intensity of the problem.

This problem of uncertainty and measurement accuracy cuts both ways too. In ideal world in which people avoided propaganda, stayed out of opinion bubbles, and sought to see things from other sides, perhaps this would all work out better. Arguably part of the problem is that people focus on the wrong side of the uncertainty. People who want to worry about the integrity of US elections (or worse yet want to try to overturn election outcomes) focus on the top end of the range of uncertainty. But they should sharply temper their claims by giving the bottom end more scope. “It could be that a lot of the evidence on self-reports of voting by non-citizens involves measurement, survey sampling error, and so forth” they should think to themselves (but often don’t seem to). On the other hand, the people who would like to dismiss the possibility that any non-citizen voting or registration occurs need to reflect on the other side of the uncertainty. It’s also possible that the estimates are closer to being right, or at least righter than they would like to believe. The fundamental point is that there’s still a lot of uncertainty in this area, and we all need to be modest about the claims we make because of it. Is there a fact check option for “we don’t know all the facts yet?”

What is different, if anything, in this analysis is that there is a bit more reason to believe that the people who said they are noncitizens really are. They were asked twice about their citizenship status, so they had a chance to correct any mistake made in reporting their citizenship status. Thus, these results from 2020 seem to indicate against the speculation that the results of the 2014 paper were driven by response error to the citizenship question.

Recent Comments